The UAE is becoming a ‘battleground’ where international and domestic banks are touting their respective services in a bid to win new trading customers. MELANIE LOVATT looks at how this competition is benefitting corporates

The UAE is becoming a ‘battleground’ where international and domestic banks are touting their respective services in a bid to win new trading customers. MELANIE LOVATT looks at how this competition is benefitting corporates

Much bank activity has centred on providing services to the Gulf region’s government- controlled oil companies. Securing this business remains important, but private sector growth and diversification of the region’s economies presents banks with more opportunities to provide transaction banking and trade financing services to a new and expanding group of customers.

This business is being fought over in the UAE. It is becoming a battleground of sorts, where international banks are pitching their global network and internet prowess against domestic banks’ long relationships with local businesses and more extensive branch network offerings. The competition has boosted the services and products offered to UAE companies. This is in stark contrast to neighbour Saudi Arabia, where even large and creditworthy companies are complaining that banks are insufficiently motivated to meet their cash and trade needs.

In the UAE, growing companies are increasingly questioning the wisdom of working with local banks when they can use an international player that has a network in place ready to service not only today’s transaction banking and trade needs, but requirements that might arise in the future as business grows.

More mid-market companies are seeking to grow their business by operating internationally, whether to reduce labor costs or expand their customer base. The internet is also serving as a vehicle to speed up globalisation, allowing companies access to customers who would have previously been out of reach.

In its latest UAE Purchasing Managers’ Index Report released in January, HSBC commented that there were further steep increases in output and new orders for non-oil producing private sector firms. In December 2014, UAE activity accelerated to the highest level in two-and-a-half years.

Lure for corporate clients

International banks are aware of the possibilities and while some have shed SME customers in the region, often because their head offices perceive them to be a riskier and more time-consuming prospect for capital allocation, they are keen to provide services to mid-market and larger companies that are expanding cross-border.

“It becomes very difficult for a local bank to get the business of a larger corporate because the international banks have a better global presence and often lower pricing,” complained a Cash&Trade source at a UAE-based bank.

Internet banking is also increasing in importance and companies with an international presence expect to be able to view and manage their accounts from their headquarters, and also allocate administration rights to their staff at their operations in other countries (see also May/June 2014 Cash & Trade – MENA banks face major challenge – for an in- depth report on transaction banking).

“The minimum that corporates expect from a channel the bank provides is that they can control their payments, receivables, balance and transaction reporting and manage their liquidity,” notes ShayanHazir, National Bank of Abu Dhabi’s executive director, commercial global transaction banking

He sees liquidity management as “the wave of the future” because larger customers are increasingly preferring to put their cashflow – including cross-border – to better use rather than taking out loans. “Local banks don’t tend to be as strong in liquidity management, particularly global liquidity management. We are at a disadvantage but we’re getting there,” he comments.

Aware that they are unable to compete with the biggest international banks on a global basis, domestic banks are increasingly staffing up to compete regionally. NBAD’s CEO Alex Thursby, who was appointed just over a year ago, believes commercial banking and trade are going to be the leading products for growth because the UAE is at the centre of the west-east corridor between Africa and China – the fastest growing area for trade in the world. “Economic and other data clearly illustrate what we have is a ‘super region’ and show that the opportunities growing in trade, commerce and investment flow across the West-East Corridor are astounding,” he says.

“The UAE is a big trade hub in the Middle East. Dubai and trade finance go hand in hand, so a lot of customers are using our trade products,” NBAD’s head of global transaction banking sales-commercial banking Gulf, Kim Tran, told Cash&Trade. Not only has the overall GDP growth in the UAE driven demand for trade finance, but also “third port” business out of free zones is also increasing. In this type of trade products do not “land” in the UAE but are sourced from, and shipped, to other destinations.

“Traders based in free zones are using trade products (like letters of credit) to structure these transactions and they need a bank to do that,” he says.

While UAE banks are increasingly able to offer customised products and services on the cash management side, Tran notes that this is more critical for multinationals. Mid-market customers “are not there yet”, he explains. While there is a “trend towards internet banking and optimisation, compared to other parts of the world, the market in the Middle East is not mature”, he adds. “Bringing in core cash management products that are used elsewhere such as in Europe and the US will help a lot of corporates,” he says. He notes that corporate customers not only need a full suite of products on the cash and trade side, but also access to loans. NBAD has recently boosted its commercial banking franchise and by covering all these bases is taking a holistic view of customer requirements, he says.

In order to compete for a share of this growing business, the larger local banks are staffing up by poaching experts from international banks. They are also increasing their product offerings. For example, National Bank of Fujairah announced the launch of its Structured Trade Commodity Financing (STCF) facility on 18 May. This is aimed at becoming a “one-stop solution” for the cross-border commodity trading requirements of companies across the UAE.

The move “underscores the bank’s rising stature as a market maker in cross-border transactions. “It used to be such that sophisticated solutions would fall under the domain of bigger, global financial institutions. NBF’s introduction of its own structured trade facility, therefore, sends a strong signal to the market of our technical competency and client focus as well as the ability to manage complex, large-scale transactions,” commented Vikram Pradhan, NBF’s head of corporate and institutional banking.

“As trade continues to open up and companies in the UAE venture into new territory, we remain committed to working closely with clients to develop innovative solutions attuned to their businesses, while helping raise awareness of the importance of this sector in the local economy,” he added. NBF boasts a growing trade financing portfolio with import and export portions rising by 12 per cent and 27 per cent respectively in 2013 compared to the previous year’s level.

International banks see the challenge. For example, HSBC has launched a commodity and structured trade finance team in Dubai. This is part of a global CSTF network of nine offices in Europe, Asia and Latin America, and the bank is now looking to field teams in Egypt, Oman and Saudi Arabia. Its move was made in response to increased demand for trade facilities and receivables finance, illustrating that in the region more sophisticated products are needed beyond standard letters of credit (LCs). Many banks support this type of business from head offices in Europe, but, by putting a team on the ground, HSBC is hoping to find an edge.

In the UAE having a good branch network gives local banks an advantage over their foreign counterparts for servicing small and medium-sized enterprises. Gulf banks have renewed their focus on this under-banked and growing sector and many are now rolling out products and services for SMEs that have typically been used only by larger companies (See the 2014 May/June issue of Cash & Trade).

Gulf banks are also in the lead for Shari’a compliant banking. Companies typically form strong relationships with Islamic banks given the “partnership” nature of the financing, and have been harder to “dislodge” by international banks offering these services through Islamic “windows” and other types of subsidiaries.

HSBC’s high-profile Islamic unit, Amanah, pared down its operations two years ago, because it was less lucrative than expected. It cut services to most countries, with the exception of Saudi Arabia and Malaysia.

However, Standard Chartered, which makes more than 90 per cent of its income from Africa, Asia and the Middle East, continues to grow its Saadiq Islamic unit, which has notched up more than $70bn in Shari’a compliant transactions. It started these services in Malaysia in 1993 and has been operating since 2003 in the UAE, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Companies bemoan KSA bank services

While banks scramble to serve UAE companies, customers surveyed in Saudi Arabia claimed they were not getting the same attention on the cash and trade side. Senior executives at large private companies operating in the Kingdom understandably preferred to speak off the record in order to give a more candid assessment of the services on offer, and attitudes to business.

They complain that both domestic and international banks prefer to service government entities such as state held oil giant Saudi Aramco, or petrochemical player SABIC, in which the government also owns a stake. Or they focus their attention on high net worth individuals.

“International banks set up shop here and decide who they will go after and it’s difficult to change their mindset,” complains an official at one large Saudi-based company. He said that they tend to prefer to offer advisory services, rather than lend money. He tried to secure loans from some international banks by offering them trade and foreign exchange business, and one lender said they could not go beyond $20m, which in transactions that worth hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars is a paltry amount.

Generally, international banks prefer to lend large sums only if it is to protect an important relationship with a major large client, agrees one Saudi banker. On the lending side domestic banks have the edge, and have been stepping up on domestic projects being implemented by large and creditworthy companies, with commitments of hundreds of millions of dollars. But outside the lending sphere, services provided by local banks are patchy, companies complain.

In this area, the previously mentioned official says international banks are out-performing their Saudi counterparts. He points out that a foreign bank operating in Saudi Arabia implemented a cash management system for his company in a matter of weeks, using a SWIFT corporate customer product.

“They did a superb job in two weeks, with something that took me six months to deploy imperfectly with local banks,” he asserts, noting that while the international bank’s work was more expensive, he was happy to pay for it because the system allowed the company to use a single interface to communicate with all of the banks it uses. This emphasised the point made earlier by ShayanHazir, of NBAD, on the growing importance of transaction banking.

In the trade sector the story is similar. Looking for discount services on export letters of credit (LCs), the executive approached a local bank. This is, of course, standard procedure, where the bank issues LCs on the back of both cash collateralisation and balance sheet lending. The local bank representative complained about the extensive documentation involved, and had to check with his legal department if he could even conduct this type of transaction. But this was a routine matter for international banks, which were eager to take on this business, said the executive.

But service has not been uniformly good from international players either. One company executive offered sizeable forex business – €50m a month – to an international bank. He was not pleased that the deal was finally rejected after six months worth of due diligence. And this is a creditworthy name and well known international brand. Another bank, US this time, professed interest in his forex business, but never got back to the company. “I have zero debt on the ventures I’m managing. I thought it was a no-brainer and that they’d take the business. That was one-and-a-half years ago and I still have not heard from them,” he says.

A senior executive at another large company operating in the Kingdom is also unhappy with the bank services on offer. “Saudi banks are seeing good rates of return on their usual lines of business, which they tend to deploy in large chunks,” he said, explaining that this has led them to shun business that takes more effort for lower return.

“Trade financing, for example, involves a lot of documentation, inspection of goods, inspection of bills of lading, so there is more complexity in this than in providing huge amounts of money at fixed returns.” He warns that while local banks’ activities could continue to bring them good returns for many years, if they want to ride out any future downturns, such as a dip in oil prices that would cut their funding, becoming larger operators in other lines of steady business such as transaction banking and trade services would serve them well.

The executive recalls that he was trying to encourage domestic banks to finance distributors of his product line. They numbered more than 30 with a cumulative portfolio of around $50m, but the domestic banks were not interested. In another case, the same executive wanted domestic banks to share credit risk for trade finance. Again, they rejected the business.

Lack of motivation

Saudi company officials note that domestic banks rarely seek to push products on them, in sharp contrast with many other countries, where there is a revolving door of callers at treasury departments touting their latest services. “I came from the US where the [bank] officers you deal with know your business better than you do. Here they’re not so motivated because there’s little competition,” explains one company official.

While the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency continues to license more foreign banks, in addition to its 12 domestically incorporated banks, international banks still in the main have only a small presence. They are smaller subsidiaries or branches of foreign banks, and largely confined to project finance, syndication activities and investment banking.

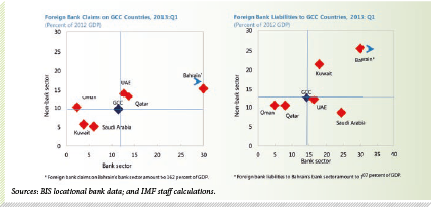

In effect, the banks in the Kingdom are more insulated from foreign competition than their UAE counterparts. GCC links with foreign banks vary considerably by country, with Saudi Arabia and Kuwait less dependent on foreign bank funding, points out the IMF in an October 2013 report on Economic Prospects and Policy Challenges for GCC Countries (see chart). However, Kuwait is less shielded because its investment corporations have greater foreign assets and liabilities.

In the Kingdom, the banks are well capitalised. Moody’s puts its asset-weighted average financial strength ratings (as of September 2013) at the seventh highest in the world. But because it is doing so well in its tried and tested lines of business, it’s thought that it does not feel the need to expand its product offering aggressively.

While it would be foolish to advocate the large bonuses that have been the subject of so much condemnation against banks in the West, perhaps a more commission-led salary structure, targeted at new businesses and customers, would help.

Opportunities are being missed, not only for the banks themselves, but also for the companies they serve. The Kingdom’s non-oil private sector is seeing healthy growth, and is poised to rise by more than five per cent this year, although it is climbing from a low base.

If banks stepped out of their comfort zones growth would probably be more stellar, although they should not take on ultra-risky business, and are right to shun the type of convoluted models based on shaky assets that led to the global financial crisis.

But, by providing more customised corporate services, they could help nurture non-oil private sector growth.

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East

Cash And Trade Magazine For Cash and Trade professionals in the Middle East